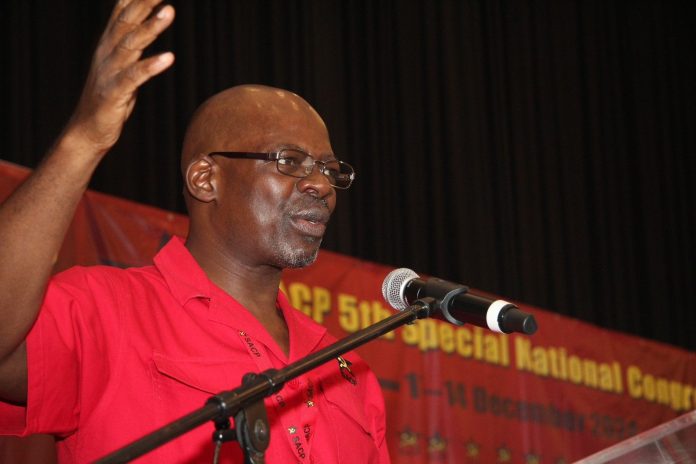

By Zamikhaya Maseti

Last week, the South African Communist Party (SACP) convened a Special Congress, igniting necessary political debates in public discourse. Of particular interest was the Party’s resolution to independently contest the upcoming Local Government Elections in 2026. Equally noteworthy was its stance on the Government of National Unity (GNU), including the decision to retain senior SACP leaders in the GNU Cabinet. This dual approach reflects a layered and, dare I say, precarious ideological position.

Predictably, the Party’s resolutions have faced a barrage of criticisms. However, a closer look at these critiques reveals a glaring lack of understanding of the South African Revolution’s theoretical foundations, particularly the Two-Stage Theory and the four pillars underpinning it. The Two-Stage Theory, central to the SACP’s revolutionary agenda, argues that societal transformation must occur in two Stages: The First: National Democratic Revolution (NDR), addressing national oppression, democracy, and inequality; and the Second, a transition to socialism, contingent on consolidating the NDR’s achievements.

Theoretically, the SACP should lead this second stage, thereby assuming primacy within the Tripartite Alliance over the ANC. However, this framework has faltered. The consolidation of the NDR remains elusive; indeed, recent developments suggest deconsolidation, particularly post-May 2024. One must question whether the delegates at the Special Congress grappled honestly with these theoretical dilemmas or simply sidestepped them. The consequences of such avoidance could be profound.

To address the intellectual shortcomings of critics—be they political analysts, social media commentators, or what I call “instant coffee intellectuals”—I will not delve into a primer on revolutionary theory. Instead, let us expose the persistent bankruptcy in their analyses and pivot to the SACP’s historical and tactical missteps. These errors are not new. The Party’s mishandling of the 1921 Rand Revolt—a moment when it failed to condemn the racist behaviors of British migrant mineworkers—remains an albatross. This misstep sowed deep ideological fractures, and the echoes of that failure still haunt the SACP’s contemporary politics.

The Tripartite Alliance has been further complicated by this historical baggage. Despite its ambitions, the SACP has struggled to assert hegemony within the Alliance. The ANC continues to be the leader of the Tripartite Alliance, a reality unlikely to change. Critics often miss this nuance: the Alliance comprises independent organizations, each with distinct ideological and constituency-driven priorities. The SACP’s critics misunderstand this complexity, focusing instead on surface-level antagonisms.

Turning to the resolutions in question, the decision to contest the 2026 Local Government Elections independently is not without a precedent. The SACP’s experience in the highly contested 2017 Metsimaholo Municipal by-election in the Free State, was a sobering one, marked by electoral underperformance and its unintended contribution to the ANC’s decline. In Metsimaholo 15 political Parties including the SACP contested 21 Proportional Representation (PR) seats and the ANC dropped by 10.5% from 45.1% to 34.5% The stakes for 2026 are exponentially higher.

With the ANC still reeling from its May 2024 electoral losses, this move by the SACP is more than a tactical gamble—it is a direct challenge. The ANC, already weakened, cannot afford such fractures within its ranks. Should the SACP’s contestation lead to further losses for the ANC, the fallout could be catastrophic.

The potential rupture of the Tripartite Alliance looms large. While the ANC has thus far refrained from retaliating against the SACP’s past electoral missteps, it may not exhibit similar restraint this time. The possibility of the SACP being ousted from the Alliance grows stronger with each antagonistic move. Such an outcome would leave the SACP in a proverbial “prisoner’s dilemma,” grappling with isolation in an increasingly turbulent political environment.

Equally contentious is the SACP’s continued presence in the GNU Cabinet. The rationale—that these leaders serve in their capacity as ANC members—rings hollow. It is a convenient technicality rather than a convincing justification. The contradiction is palpable: how does the Party reconcile its disdain for the GNU with its willingness to maintain a presence within it? This ideological paradox undermines the credibility of its resolutions and casts doubt on its ability to navigate the troubled waters ahead.

The rupture of the Tripartite Alliance seems inevitable. The SACP faces a critical juncture in its history. Will it chart a course toward ideological clarity and organizational independence, or will it continue to drift in an ideological quagmire? The answers remain unclear, but one thing is certain: the road ahead for the SACP will not be an easy one.

Zamikhaya Maseti is a political economy analyst based in Pretoria, South Africa