By Cultural Consulate of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran

In the vast constellation of global literary giants, few shine as enduringly as Abu al-Qasim Firdowsi, the Persian epic poet whose masterpiece, the Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”), has preserved the Persian language and spirit for over a millennium. From a South African perspective, Firdowsi’s legacy transcends geographic and temporal borders. He represents the resilience of cultural identity, the power of the spoken word, and the role of the poet as a guardian of national memory—values echoed deeply in South Africa’s own journey of resistance and renaissance.

A Poet of Resistance and Revival

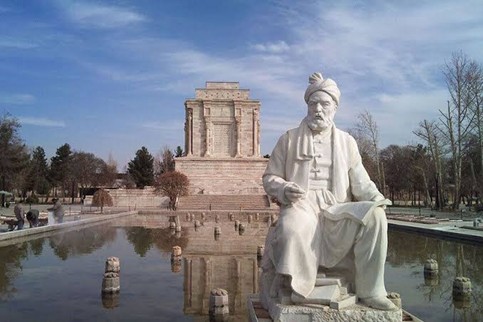

Born in the 10th century in Tus, Iran, Firdowsi lived during a time when Persian culture was under the threat of Arabization following the Islamic conquest. Arabic had become the dominant language in administration and literature. Yet, Firdowsi, with unwavering devotion to his native tongue and cultural heritage, composed the Shahnameh—an epic of more than 50,000 couplets in Persian—that revived pre-Islamic history and mythology.

This act of cultural preservation resonates strongly with South Africans who, under colonial and apartheid rule, faced the systematic suppression of indigenous languages, cultures, and narratives. Just as Firdowsi safeguarded the soul of Persian civilization through his poetry, South African poets, oral historians, and artists became custodians of memory and resistance.

Storytelling as a Weapon of Liberation

The Shahnameh is more than an epic; it is a historical consciousness shaped by storytelling. It celebrates heroes such as Rustam, Sohrab, and Zal, whose tales reflect themes of justice, honor, and moral struggle. In many South African communities, especially among the isiXhosa and isiZulu peoples, oral traditions like imbongi (praise poetry) have long served a similar role: to inspire and to uphold communal values.

Both Firdowsi’s Persian tradition and South Africa’s indigenous poetic forms view the poet not as an entertainer, but as a truth-teller—a voice for the voiceless. In the post-apartheid era, South Africa has recognized this powerful tool, using literature and performance to rebuild a fractured society. Firdowsi’s Shahnameh teaches that historical memory can heal, empower, and unite.

Linguistic Sovereignty and Identity

Firdowsi famously rejected courtly pressure to write in Arabic, remaining loyal to Persian. This linguistic choice was political and poetic. In postcolonial South Africa, similar efforts have been made to uplift indigenous languages, such as isiZulu, Sesotho, and Xitsonga, within education and literature. The broader goal in both contexts is clear: to assert identity and reclaim narrative authority.

Firdowsi’s work stands as a monument to the idea that language is more than communication—it is memory, pride, and resistance.

Shared Cultural Wisdom

Both the Islamic Republic of Iran and South Africa are nations steeped in ancient wisdom and diverse traditions. Their histories are marked by conquest and resilience, foreign domination and cultural resurgence. In this light, Firdowsi is not just a Persian poet, but a universal figure. His commitment to truth, beauty, and cultural sovereignty mirrors the values of many South African intellectuals, from Steve Biko to Mazisi Kunene.

A partnership between Persian and South African cultural institutions could illuminate these shared values and promote cross-cultural understanding. Introducing Firdowsi’s poetry into South African academic curricula or arts festivals could offer students a comparative lens to study how epic literature shapes national consciousness.

Conclusion: Firdowsi’s Message for South Africa

From the valleys of Tus to the townships of Soweto, Firdowsi’s message endures: a nation’s soul is safeguarded by those who dare to preserve its story. In our own struggle against erasure and inequality, South Africans can look to Firdowsi as a poetic ancestor—one who reminds us that the pen, like the spear, defends the dignity of a people.

In celebrating Firdowsi, we celebrate the universal power of literature to overcome oppression, to dignify language, and to remind us that cultural heritage is not a relic of the past, but a living, breathing force of liberation.

Cultural Consulate of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran.