What makes a public space truly public?

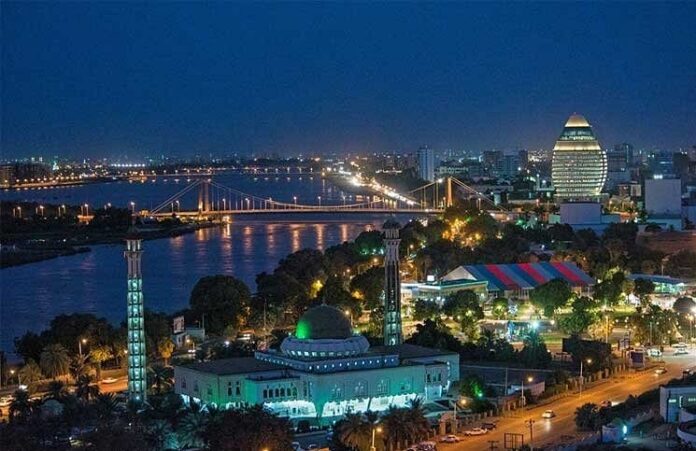

In Khartoum, before the current conflict engulfed Sudan, the answer was not always a park, a plaza or a promenade.

The city’s streets, tea stalls (sitat al-shai), protest sites and even burial spaces served as dynamic arenas of everyday life, political expression and informal resilience.

In a recently published article, I studied 64 public spaces across pre-war Greater Khartoum, revealing a landscape far richer – and more contested – than standard urban classifications suggest. Specifically, I uncovered four classifications: formal, informal, privately owned and hybrid spaces – each alive with negotiation and everyday use.

While some spaces were planned by colonial engineers or municipal authorities, many were carved out by communities: claimed, adapted and reimagined through use.

My research offers valuable insights into the design and planning of Africa’s cities. As they grow and face mounting political and environmental pressures, it’s time to rethink how public spaces are defined and designed – not through imported models, but by listening to the ways people already make cities public.

Across the African continent, cities are growing fast – but not always fairly. Urban expansion often privileges gated developments, mega-projects and high-security zones while neglecting the everyday spaces where most people live, work and gather.

In Sudan, these dynamics have been further complicated by conflict, displacement and economic instability. The ongoing war has disrupted not only governance, but also the spatial fabric of urban life.

My paper aims to invite those involved in planning policies and post-conflict reconstruction to move beyond formal, western-centric models that often overlook how publicness actually unfolds in African cities: through informality, negotiation and social improvisation.

Khartoum’s public spaces, as documented in my study, serve as diagnostic tools for understanding how cities survive crises, express identity and contest inequality.

In the wake of war and displacement, these spaces will play a role in shaping how Sudan rebuilds not just infrastructure, but social cohesion.

Pre-war Khartoum

Khartoum’s public spaces cannot be understood through conventional categories – like formal squares and urban parks – alone. These formal squares represent only one layer of a much more plural and negotiated urban reality.

Drawing on fieldwork and the documentation of 64 public spaces across Greater Khartoum, I identify four overlapping types that reflect how space is produced, accessed and contested.

1. Formal public spaces: These include planned parks, ceremonial squares, civic plazas and administrative open spaces, often relics of colonial or postcolonial urban planning. They are defined by order, visibility and regulation. Mīdān Abbas, originally an active civic space in the centre of Khartoum, repeatedly reclaimed by informal traders and protesters, is one example, illustrating how even the most formal spaces can become contested. It was notably active during Sudan’s April 1985 uprising, serving as part of a wider network of civic spaces used for political mobilisation. Informal traders consistently transformed it into a bustling marketplace, embedding everyday commerce and social exchange into the formal urban fabric.

2. Informal and insurgent spaces: These emerge beyond or against official planning logics – riverbanks used for gatherings, neglected lots transformed into social nodes or bridges appropriated by traders. They include spiritual sites like Sufi tombs, and protest spaces such as the sit-in zone outside the city’s army headquarters. These spaces reveal the city’s capacity for bottom-up urbanism and collective adaptation.

3. Privately owned civic spaces: Shopping malls, privately managed parks and cultural cafés fall into this category. While they appear public, they are often classed, surveilled (monitored through cameras or security presence) or exclusionary. The rise of these spaces coincides with the decline of state-managed urban infrastructure, reflecting the turn in Sudanese urban governance.

4. Public “private” spaces: These spaces blur lines between ownership and use. They include mosque courtyards, school grounds, building frontages or underutilised university lawns that serve as informal gathering points. Access here is governed less by law and more by social codes, trust or class.

Together, these typologies highlight that “publicness” in Khartoum is relational. It depends not only on who planned a space, but who uses it, how and under what conditions.

Planning in African cities must therefore move beyond fixed zoning maps to embrace the layered, fluid and lived nature of urban space.

Rebuilding, rethinking, resisting

Post-conflict reconstruction in Sudan – and elsewhere in Africa – must resist the allure of “blank slate” master plans. Those involve rebuilding cities from scratch with sweeping, top-down designs that ignore existing social and spatial dynamics.

Imported models, often guided by bureaucratic thinking or commercial incentives, risk erasing the very spaces where public life already thrives, albeit informally or invisibly.

Rather than imposing formality, planners should recognise and strengthen the informal and hybrid systems that sustain civic life, especially in times of instability.

Urban theorists working in and on the global south, such as AbdouMaliq Simone and the late Vanessa Watson, have long argued for planning frameworks that centre on everyday practices, adaptive use and spatial justice.

Khartoum offers a compelling case.

From the sit-ins of 2019 to tea stalls run by displaced women, public spaces in Sudan are not inert backdrops. They are active platforms of everyday life, resistance, care and community-making.

Reconstruction must begin by asking: what spaces mattered to people before the war? Which ones fostered inclusion, dignity and visibility? Only then can new urban futures emerge, ones that are rooted in the practices of those who have always made the city public, even when the state did not.

What makes spaces truly public?

The public realm in Sudan has always been shaped through negotiation, sometimes with the state, often despite it.

Rebuilding after war is not only about reconstructing buildings but also about reimagining the terms of belonging.

This requires a shift from viewing public space as a fixed asset to understanding it as a dynamic process. Who gets to gather, to speak, to rest, to protest – these are the true measures of publicness.

Understanding Khartoum’s pre-war public spaces isn’t a nostalgic exercise. It’s a necessary step towards building more inclusive, resilient and locally grounded cities in the wake of crisis.